Victoria Dos Santos

(Università di Torino)

The ubiquity and mediation of digital technologies in the cultural scenario have produced changes in the way of inhabiting the contemporary panorama, not only by disrupting and reformulating communicative processes and human interactions but by rethinking how people relate with the digital universe and its complex dynamics. In this scenario, the dialogues between religious imaginaries and the digital medium have been intensifying. Such intersections allow making visible the impact of virtual networks in the sphere of the sacred (Wertheim 1999), the numinous and the magical, as well as the potentialities of meaning that these worlds acquire when they come into contact, since “the two are now converging on one another.” (Hoover 2012: 30). In this sense, the magical and cosmological component that seemed to have disappeared during modernity has been re-proposed within one of the greatest technological innovations of humanity: the digital machine (Aupers 2009).

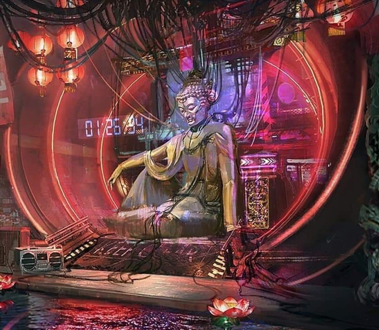

The discourses about the links of digital technology with the spiritual contexts can however be very versatile, affecting how beliefs are perceived by opening the possibilities for emerging nontraditional beliefs and religious systems. That is to say, the internet allowing new forms of expression through the own characteristic of digital spaces – for example, its fluid nature – providing new ways to experience spirituality. One of those emerging phenomena is what is known as Technopaganism (TP), a term that became very popular during the ’90s, especially in the Californian cyberculture, bringing together contemporary paganism, shamanism, popular culture, and science fiction. In its beginning, Technopaganism aimed to consciously ritualize cyberspace (Campbell 2005), while considering the “technological surroundings as an intelligent, autonomous force” (Aupers 2002: 199).

Technopaganism never had a single definition since its limits are blurred. However it is possible to recognize two different paths of this spiritual phenomenon: The first one belongs to neopagans migrating their practices online, where the eclectic and complex contemporary pagan cosmology found a perfect scenario to settle and expand by using digital artifacts to rewrite its practices. The second belongs to techno-enthusiasts who saw a parallelism between magical practices and cyberspace, allowing other dimensions of reality to take place. The programmer Mark Pesce[1] was one of the greatest exponents of this second scenario involving esoteric conceptions with computers. On that matter, when thinking about technopaganism as a whole, technology and spirituality are related in such a way that they work as an inseparable unity, keeping “one foot in the emerging technosphere and one foot in the wild and woolly world of Paganism” (Davis 1995).

Even if the term became obsolete after the first decade of the ’00s many contemporary practices include directly or implicitly a ‘technopagan aura’, considering how the halo of mysticism surrounding digital technologies seemed to be reemerging within the posthuman postulates and the advances in artificial intelligence, robotics, and immersive extended realities. Nowadays, people that recognize themselves as technopagans inhabit all kinds of virtual spaces to develop their beliefs and spiritual practices. One of those territories is represented by virtual communities and video games, “the medium that best epitomizes the combination of technology and spiritualist narratives” (Tanaka 2015). However, what better describes the current technopagan condition is how it allows to reconstruct or simply reinvent aspects of people’s spiritual life through an animistic[2] ontology (Descola 2005) in regards to other beings, entities, and forces, including machines and technological devices (Cowan 2005: xi). For a technopagan view, therefore, the online context is an organic environment where individuals can develop valid spiritual experiences, together with virtual entities – as avatars – and algorithmic processes.

[1] The first written record of TP is an interview to Mark Pesce, published by Wired magazine in 1995, where he explains how digital technologies are not only a form of magic but a door to access other planes of connection and a place to meet the divine. As stated by Pesce: “I think computers can be as sacred as we are, because they can embody our communication with each other and with the entities – the divine parts of ourselves – that we invoke in that space” (Davis 1995).

[2] According to Phillipe Descola, animism can be understood as an ontology characterized by ‘a continuity of souls and a discontinuity of bodies’ between humans and nonhumans (2014: 275). Each animistic being possess a soul or vital life force. The conception of animism in anthropology was introduced by Edward Tylor, for whom according to Tylor, animism is a form of religion in which the spirits and souls of humans and other beings or entities are necessary for life, therefore the soul is not only a vital force to specific beings but is pervasive throughout the cosmos and imbued in all beings (1977 [1871]).

References

Aupers, S. (2009). “The Force is great: Enchantment and Magic in Silicon Valley.” Masaryk University Journal of Law and Technology 3(1): 153-173.

Aupers, S. (2002). “The revenge of the machines: On modernity, digital technology and animism.” Asian Journal of Social Science 30(2): 199-220.

Campbell, H. (2005). “Spiritualizing the Internet: Uncovering discourses and narratives of religious internet usage.” Heidelberg Journal of Religion on the Internet 1(1): 1-26.

Cowan, D. (2005). Cyberhenge: Modern Pagans on the Internet, New York, Routledge.

Davis, E. (1995). “Technopagans: May the Astral Plane be Reborn in Cyberspace.” Wired magazine. https://www.wired.com/1995/07/technopagans/.

Descola, P. (2005). Par-delà nature et culture Vol. 1, Paris, Gallimard.

Hoover, S. (2012). “Religion and the Media in the 21st Century,” Trípodos 29: 27-35.

Tanaka, R. (2015). Technopaganism and the Newer Age, available at www.ribbonfarm.com/2015/05/13/technopaganism-and-the-newer-age/

Tylor, E.B. (1977). Primitive Culture Vol. 1. Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art and Custom. New York: Gordon Press.

Vecoli, F. (2013). La religione ai tempi del Web. Roma/Bari: Laterza.

Wertheim, M. (2000). The pearly gates of cyberspace: A history of space from Dante to the Internet. New York: WW Norton & company.

Victoria Dos Santos is a PhD student in Semiotic and Media at the University of Turin. Her areas of research are about emerging religious practices in the digital space, neopaganism, semiotics, and digital media studies. She is holding a degree in Communication Science, at the Catholic University Andrés Bello (UCAB) in Caracas, Venezuela. She got a master in journalism from the University of Barcelona and the University of Columbia in New York.